Three-year-old Jane Kveton

doesn’t care for the pieces of grass that float on the water and stick to her feet. As her father, John, turns the well on to water the lawn with irrigation pipe, she avoids the yard, running up and down the sidewalk splashing in the puddles.

Eight-year-old Jane

grips a sawed-off hoe handle on the family farm. The West Texas sun beating down on her as she weeds the “longest row in the world.” She’s not really a fan of the outdoors, and her family lovingly refers to her as “Princess Jane.” Her Czech grandfather, Fred, shows up in the late afternoon to give her and the rest of the Kveton children peaches and beer to take home — much to the chagrin of Jane’s mother.

At 18 years old,

Jane is the 10th child her father will have sent to college. To help fund this endeavor, she applies for a scholarship with Southwest Textiles Inc. — a textile mill in Abernathy, Texas, where she and her family live on a 160-acre cotton farm. Receiving the scholarship meant earning her degree in textile engineering technology at Texas Tech University.

Her first class at TTU, the textile engineering department head asked how much a cotton bale weighed. Jane, who had grown up on a cotton farm, had no idea. “I knew how to hoe it, I didn’t know much about what happened after that,” Jane added. The professor chastised her in front of the entire class for growing up on a cotton farm and knowing so little about it. Joke’s on him.

Jane, now 20 years old,

is introduced to Roger Milliken — owner of the largest privately owned U.S. textile enterprise at the time — who is trying to recruit students to work at his new prestigious research facility. Except, he wanted them to research fiber replacements for cotton, because “it’s such a pain for the mills.” This was the first time Jane felt a passionate connection to cotton and began to realize how it had shaped her life up to this point.

22-year-old, Jane

graduates with her textile engineering degree and is accepted into an exclusive master’s degree program with the Institute of Textile Technology in Charlottesville, Virginia. They only accepted 10 students per year. She was the only TTU student selected and her department head was so excited. But Jane had other plans, wryly saying, “I decided to get married instead.”

Jane married James Dever in 1983 and the couple stayed in Lubbock. James worked for the Coca-Cola bottling company, while Jane had plans to follow her mother’s occupation as a partner to her husband at home. Her housewife status lasted four months.

Dr. John R. Gannaway had recently become the cotton breeder at the Lubbock Texas Agricultural Experiment Station and ambitiously had more than 1,000 crosses in the field in 1983. They were overwhelmed and needed help. One of the student workers from Texas A&M that was helping at the center that summer had grown up with Jane in Abernathy. “Can you come in and help self-pollinate?” he asked Jane on the phone. “You can be parttime and just help glue flowers shut in the afternoons.”

Video: Why Jane Loves Her Work.

At 22 years old,

Jane is a student worker at the Lubbock center and still has no idea who Dr. Gannaway is. She comes in at 1 p.m. — enters the lab, grabs her paper, tags, blue apron — and glues cotton blooms shut until 5 p.m.

One day while working, Jane is told, “Dr. Gannaway wants to see you.” When she entered his office, he held up a newsletter from the Texas Tech Textile Research Center and said, “Is this you?” She looked at the paper. It was titled, “Textile Topics,” and read, “Jane Kveton, winner of the Textile Veterans Association Award.” She was also named one of TTU’s outstanding engineering students. Her picture was at the top.

“That’s me,” Jane replied. “Kveton is my maiden name.”

“You have a degree in textiles?” Dr. Gannaway asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you know anything about fiber quality?” he asked intensely.

“Of course,” she responded.

At the time, Gannaway was working with Joel Hembree with PCCA, Rex McKinney with Farmers Cooperative Compress and Don Johnson with Plains Cotton Growers Inc. to establish the Plains Cotton Improvement Program (PCIP). Jane was asked to help write up a fiber quality proposal for PCIP in 1983. While she initially worked on fiber quality projects at the Center until 1993, Jane would continue to follow the program for four decades, eventually coming back in 2008.

Between 1993 and 2008, Jane worked for the Textile Research Center at TTU, PCCA, BioTex, held a 25% appointment with the Extension AgriPartners program, and spent 10 years as an agronomist and global cotton breeding manager for FiberMax cottonseed. When John Gannaway retired in 2008, she returned as the Project Leader of the Lubbock Center cotton breeding program.

It’s 2023, Jane is working through her 42nd crop,

with a passion that has been aflame since childhood. We could go into great detail on Dr. Dever and her 42-year career that helped transform the Texas High Plains cotton industry. But the stories below are what make her Jane.

The Stories of Jane

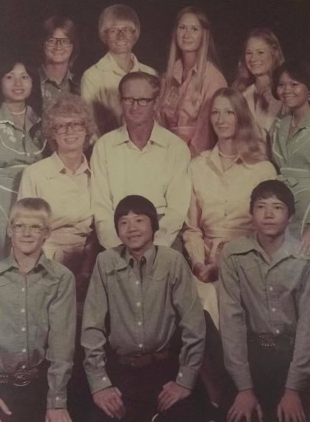

The Kveton Siblings

When Jane showed up for class as a freshman at New Deal High School in 1975, news was spreading through the halls like wildfire. “We have new students this year,” one said, looking down the hall. “Four

The Kvetons

Vietnamese kids are going to be in school with us!”

That’s a big deal for a small rural town, where many had never been beyond Lubbock, much less another country. All four of the new students were close in age to the four youngest Kveton siblings and Jane quickly became friends with Ninh. He was shy and reserved like her and they hit it off almost immediately.

Jane came banging through the screen door one day after school, calling for her mom.

“Mom, Ninh didn’t come to school today.”

“Mama Jean,” as she was lovingly referred to, decided to investigate.

Turns out, the four new Vietnamese students were in the foster care system and had saved their lunch money for months to escape a bad situation. They didn’t get far before they found themselves on a 160-acre farm in Abernathy, Texas, surrounded by Czech farmers.

The foster care system was trying to find a family to place them with, but no one wanted to take all four of them together.

“They’ve been split up enough,” Mama Jean told the social worker. “They can all come home with me.”

So, in December of that year, they did just that. John Kveton used to tell anybody that would listen, “I came home from harvesting cotton one day and had four more kids somehow.”

They were the four oldest siblings of a family of eight, whose father — an officer in the South Vietnamese army — was killed at the end of the Vietnam War.

These four children, Hue, 17, Hoa, 16, Ninh, 14 and Thanh, 12, were sent to America by their mother, Qui, who hoped they would have a better life. John and Jean Kveton helped give them that.

These were the first four children the Kvetons officially fostered. They had already opened their home to their children’s friends, relatives, and relatives of friends. In all, the Kvetons claimed 23 children for their own — six biological and 17 of the heart. To this day, they still have big family reunions where they get together once a year.

Kveton Sibling Reunion 2023.

The Lost Art of Hoeing Rows

Before the glory days of cotton resistant to glyphosate, glufosinate, 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and/or dicamba, the main weed management system was hoeing. And if you grew up related to a farmer, you

Jane with a hoe at the Lubbock Center in 2021.

would find yourself on the hoeing crew. Before Jane could do much else, she was removing weeds in cotton fields using a hoe with the handle shortened to accommodate her small stature.

When Jane was a graduate student and research assistant at the Texas A&M AgriLife Lubbock Center, weeds had to be top of mind at every turn. When working on genetic improvement before herbicide tolerant traits are incorporated, researchers engage in what Jane refers to as “1970 farming.” Without GE herbicide technology and limited availability of residuals that would not mask genetic differences, there is only tillage and hard work are the only tools for weed management.

Her first year at the center, in 1983, field bindweed was a serious problem for producers and researchers alike. There was no killing it. Once it came up, you had to dig it out of the ground, or it would immediately take over the entire field.

One of Jane’s first memories at the Lubbock Center is going out every morning with a trowel, bucket and trash bag with instructions from her boss, Dr. John Gannaway. They had the same routine every day:

– Dig, dig, dig out the bindweed,

– Place in trash bag,

– Tie up the trash bag really tight

– Throw in dumpster

– Repeat

The Kvetons didn’t have bindweed on the farm, so Jane thought the whole process was ridiculous. Turns out, her father John and Uncle Henry would hoe weeds right when they came up, so, of course, she didn’t grow up with bindweed. They were coined the “Gardener Farmers” for a reason.

And, while herbicide technology has been a great blessing to producers in the area, it’s also turned hoeing into a lost art.

“When you have herbicide technology in the seed and/or spray applications of it on your fields, you may not see any weeds,” Jane said. “However, with fields so clean, producers may not be paying attention to the sides of the roads surrounding their fields and those weeds can creep in.”

And, as she learned with the bindweed in 1983, once the weeds are in, they’re incredibly difficult to remove. Her experience came back full circle in 2019 as weeds infiltrated some trial plots. Jane gathered her team together.

“I’m so sorry,” she told them looking around the room, “but we’re fixing to have to dig weeds out of rows to fight this infiltration. You see in 1983, Dr. Gannaway showed us…”

Researcher Carol Kelly digging out bindweed in 2019 with Jane.

For the first two months of any summer student’s tenure at the Center, they have to hoe. “I always tell the students, ‘You think you’re never going to get on top of it, but you will have solid weed control if you just stick with it the first month or two,’” Jane added.

One morning, Jane comes in grabs a hoe and heads out to the field. All of a sudden, she looks up to find a student hoeing on her row.

“Why are you on my row,” she asked him.

“Oh, we’re just hoeing the weeds we can see from the road,” he responded.

And that day, all the students learned a very important lesson from a usually elegant Jane Dever who takes hoeing very seriously.

New Mom at 58

Jane’s husband James is a caretaker by heart. He’s taken care of their parents as they grow older and always helped look after his older sister’s children. They were very close with one of his nieces named Megan. Megan lost her husband when the kids were young to a brain aneurysm, so Megan’s children, Catherine and Mikayla, would all come over to Jane’s house for dinner after school frequently while Megan worked.

In 2019, Megan and Catherine were in a horrible car accident. Megan didn’t make it. In the blink of an eye, Jane found herself the legal guardian of two teenagers experiencing tragic loss.

Much like her parents did many years ago, Jane and James never gave it a second thought when it came to bringing Catherine and Mikayla into their home. In fact, they left their cozy two-bedroom townhouse and moved into a three-bedroom apartment in Lynwood to accommodate everyone.

Catherine and Mikayla have since graduated high school and started their own independent lives; however, they always know they have a home to come back to. Because much like her parents did for their children, Jane and James will always be “home” for them.

'My Research Doesn't Belong to Me. It Belongs to Texas High Plains Cotton Producers.'

Jane and I are sitting in my office. She’s just told me that she’s leaving.

Jane is retiring from Texas A&M AgriLife Lubbock Center — her last day will be February 29. She is moving to Florence, South Carolina, to be the new Director of the Pee Dee Research & Education Center at Clemson University.

I asked her how she felt about leaving her breeding program. I assumed she felt ownership of it with all that she’s accomplished over four decades.

This was her response and sums up the Jane that you and I are going to miss terribly.

“I don’t consider it my program or my people. My fondest dream is to have enough money to develop an endowed chair for this position. But it wouldn’t be named the Jane K. Dever Endowed Chair in Cotton Breeding. I would want to name it the Plains Cotton Endowed Chair in Cotton Breeding, because that’s who that program belongs to. Not me. It belongs to the producers of this great region, the Texas High Plains.”

We wish Jane the best of luck in her new adventure and words cannot express the impact she has had on the Texas High Plains cotton industry.

“My heart is in the High Plains of Texas where I first fell in love with the science of cotton breeding.” – Jane Dever, Ph.D.