His name was Ferdinand Valentine Kveton, but everybody called him Fred.

Fred Kveton. Source: Texas Agricultural Extension Service – “The Extensioner” November 1949.

Born in Moravia, Czech Republic, 12-year-old Fred followed his older sister to America in 1908, settling near San Angelo. He would go on to fight in World War I, earning his U.S. citizenship. In 1924, he took his military service earnings and bought 160 acres of land in Abernathy, Texas.

He farmed that tract of land with his sons John and Henry Kveton till the day he died in 1990.

In the November 1949 issue of “The Extensioner,” a publication by Texas Agricultural Extension Service, Fred was featured for his innovative practices on the farm. The headline read, “A 480-Acre Farm on 160 Acres — The Kvetons of Lubbock County Triple Yields with Irrigation and Mechanization.”

The article sheds light on who Fred was and how he farmed. The author thought highly of him as he states:

“Fred Kveton is a progressive farmer, but he is also a cautious man. He is not one to change from a practice or systems that has worked for him over a period of years until he is convinced that a new system will do better; that it will increase his yields, make more profit, cut down his costs, save labor or is better for his land. You won’t find Fred Kveton plunging into cotton this year or wheat the next or taking a flyer in commercial vegetables. When a farmer does that, Mr. Kveton will tell you he’ll usually find that he’s a ‘year behind the market.’”

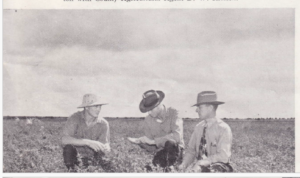

John and Henry Kveton with County Agricultural Agent D. W. Sherrill. Source: Texas Agricultural Extension Service – “The Extensioner” November 1949.

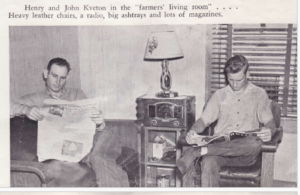

Fred passed this approach to his sons — John and Henry took the 160 acres of farmland and turned it into 2,000. They were known as the “gardener farmers,” as keeping the rows clean of weeds was somewhat of an obsession. They never wanted to acquire more land than they could keep up with, nor did they want to live beyond their means.

Lucky for John, he had 23 children to help him hoe those rows.

John and his wife, “Mama Jean,” fell into foster parenting by accident, becoming caregivers for four Vietnamese children in 1975 while also taking care of six biological children. This started a foster parent journey that continued for decades. John put all of his children through college, and you would often hear him saying, “I have spent my life paying for food and education.”

The Kveton kids did not squander this education. Of the original foster children, No. 4 son, Thanh Ho, would appear

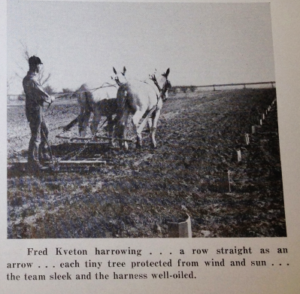

“Fred Kveton harrowing a row straight as an arrow. Each tiny tree protected from wind and sun. The team sleek and the harness well oiled.” Source: Texas Agricultural Extension Service – “The Extensioner” November 1949.

in a UT Southwestern article in 2011. As a mechanical engineer, he went all over the world designing clean rooms for Intel Corporation. When asked about his success, he said he learned the value of work ethic from his father — who was a great farmer.

No. 1 sister is an oncology nurse, No. 2 sister retired as a captain in the U.S. Navy, No. 3 brother retired as a Master Sergeant from the U.S. Air Force and now works for the Federal Aviation Administration. All very accomplished. Earning those accomplishments through grit learned on the farm.

That doesn’t take away from the fact that it was a hard life. His children still vividly remember him driving a 1973 Ford LTD Station Wagon until the wheels absolutely fell off, because that year “was the last year I made money farming.” It was also the year he first sent three kids to college, including his oldest, Kit. She wanted to farm, but, after the education investment, John told her she was not smart enough to be a farmer and should go to medical school instead. She delivered roughly 4,000 babies before retiring this March.

Every Kveton child worked on the farm. They hoed weeds with sawed off hoe handles and helped with planting and harvest. If they accidentally hoed cotton instead of weeds, Uncle Henry would get his calculator out and show them how much money they had just lost. They worked hard and many of them had a passion for the farm.

Every Kveton child worked on the farm. They hoed weeds with sawed off hoe handles and helped with planting and harvest. If they accidentally hoed cotton instead of weeds, Uncle Henry would get his calculator out and show them how much money they had just lost. They worked hard and many of them had a passion for the farm.

No. 10 sister; however, didn’t care as much for the outdoors as the rest of her siblings. She was the last person expected to go into agriculture.

Growing up, they called her “Princess Jane,” but you and I know her as one of the greatest cotton breeders of our time. Stay tuned for the next installment of our Faces of Cotton story series on Jane Kveton Dever.